Refresh:

While many think that a menstrual cycle is signified by a period once a month, it is much more complex. The connection between the brain, ovaries, uterus, and hormones creates a harmonious symphony of the female body, regulating the menstrual cycle, nurturing reproductive health, and delicately balancing the body’s hormonal system. The menstrual cycle is typically 28 days long but can vary between 21 and 40 days for different women. The entire cycle can be divided into two cycles: the uterine cycle and the ovarian cycle.

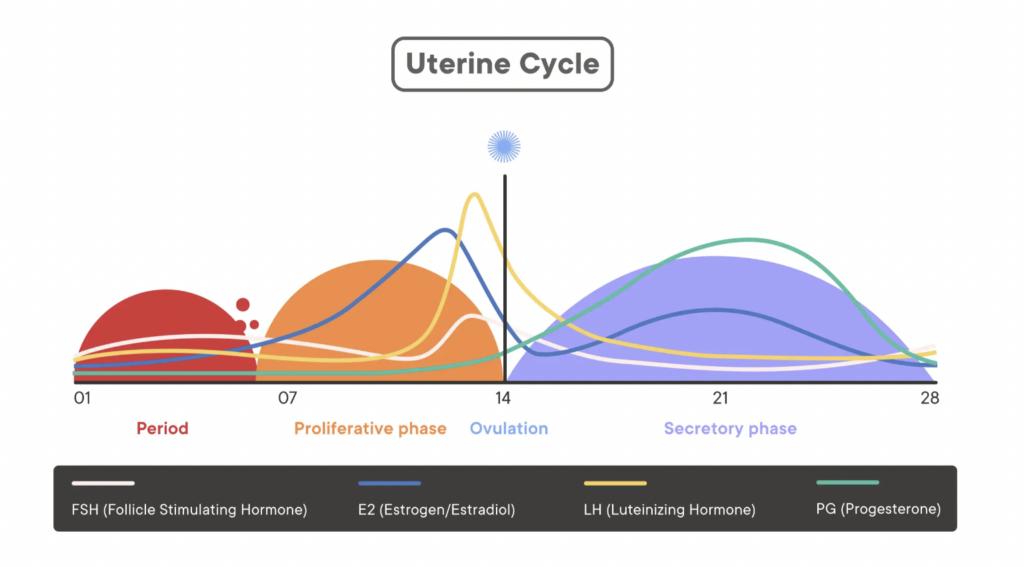

The uterine cycle encompasses the physical changes of the uterus, more specifically, when the uterine lining thickens and sheds. It can be further broken down into three stages: the period, the proliferative phase, and the secretory phase.

- Menstruation, or the period, lasts from the time vaginal bleeding starts until the time it ends. The blood from the previous cycle is shed during this phase, lasting about 5-7 days.

- Estrogen and progesterone are at their lowest (causes the endometrium to shed its lining)

- The proliferative phase lasts from the end of the period until ovulation. During this phase, the uterus lining, or endometrium, thickens in preparation for a potential fertilized egg to grow.

- Estrogen begins to rise (signals endometrium to thicken)

- The secretory phase lasts from ovulation until the start of the next period. During this phase, the endometrium prepares itself for pregnancy or breaks down for the next period.

- Progesterone rises (stops thickening of endometrium)

- Prostaglandins (causes the uterine muscles to cramp) begin to increase if the egg is not fertilized.

Illustrations by Marta Pucci & Emma Günther

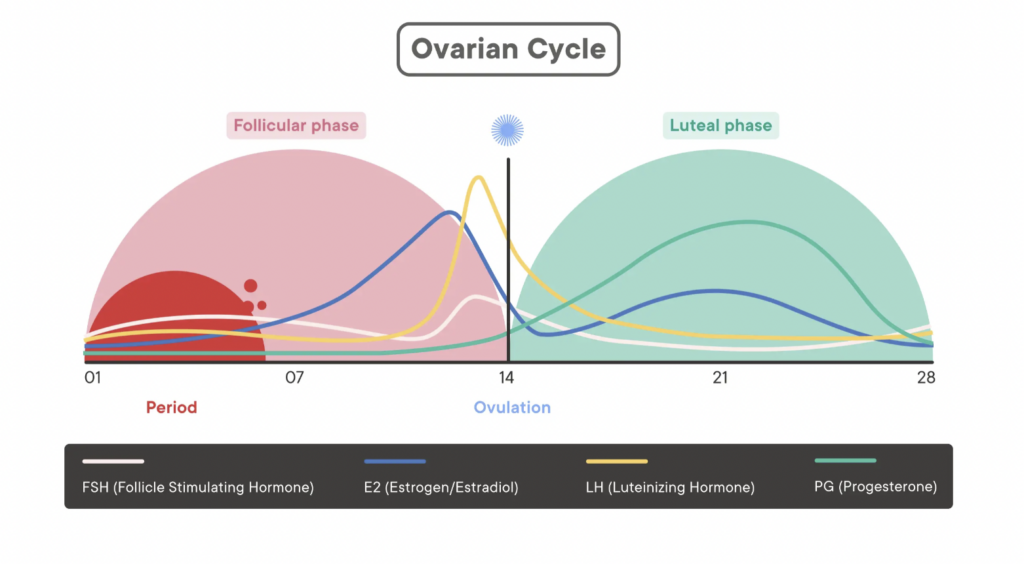

The ovarian cycle creates physical changes in the ovaries, causing the preparation and release of eggs. It can also be broken down into two stages: the follicular and luteal phases.

- The follicular phase lasts from the start of the period until ovulation. During this phase, a follicle within the ovaries becomes more dominant and prepares to be released at ovulation.

- The pituitary gland releases follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) (allows ovaries to prepare egg for ovulation)

- The dominant follicle produces more estrogen as it grows. Estrogen peaks right before ovulation

- The luteal phase lasts from ovulation until the start of the next period. The released follicle turns into a corpus luteum, which, if fertilized, supports the hormones during pregnancy. If the corpus luteum is not fertilized, it will break down.

- If the egg is not fertilized, then progesterone will peak and then drop, while estrogen will also rise and then fall (both cause onset of period)

- Note: The hormonal changes in this phase are what cause common premenstrual syndrome (PMS) symptoms.

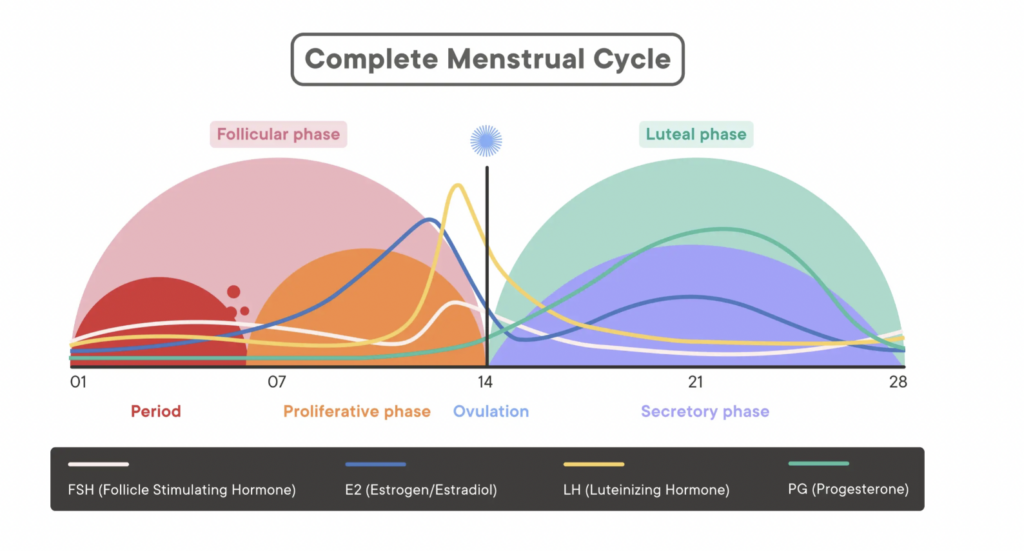

Here is a complete diagram of the menstrual cycle.

Note: If you are on any hormonal birth control, the nature of your cycle will be different from a natural cycle. This work focuses on the natural cycle, so the topic of hormonal birth control is not included in this project’s scope. For more information, here are several sources:

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7497464/

- https://onewelbeck.com/news/how-different-contraceptive-methods-affect-periods/

How to Track Your Cycle:

The menstrual cycle lasts on average 28 days, but it is normal to fluctuate between 21 and 35 days. You can track your period in a calendar, but I find apps like Clue or Flo very helpful for deciphering my cycle length and phases. (Fehring)

Why Is It Important?

Hormones are chemicals that act as messenger molecules in the body and are responsible for controlling:

- Metabolism

- Homeostasis

- Growth and development

- Sexual function

- Reproduction

- Sleep-wake cycle

- Mood

- Stress-response

As you can see, hormones control every aspect of our lives. Regulating hormones is essential to maintaining these functions properly. Hormone regulation is also crucial for female athletes as it regulates energy levels during exercise/training, helps with muscle growth and repair after exercise, and improves bone density.

When the hormones are not regulated properly, then hormone imbalances can occur. This happens when there is too little or too much of a hormone, which can cause conditions such as:

- Irregular periods

- Infertility

- Acne

- Diabetes

- Thyroid disease

In female athletes, this can also lead to an increased risk of injury and decreased performance.

Several years ago, I struggled with my performance. I was experiencing frequent injuries, constant low energy, and painful and irregular periods. I was desperate to make a change, and I discovered that I could ease my symptoms by helping my body balance its hormones again. The most significant factors that helped me to balance my hormones were proper nutrition, recovery, adequate sleep, and stress management. Once this was sorted out, I could train more effectively, and results in my performance soon followed. I will detail these strategies in the tabs Training, Nutritional Needs, and Lifestyle.

Citations:

Fehring, R. J., Schneider, M., & Raviele, K. (2006). Variability in the phases of the menstrual cycle. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 35(3), 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00051.x

Downie, J., Poyser, N. L., & Wunderlich, M. (1974). Levels of prostaglandins in human endometrium during the normal menstrual cycle. The Journal of Physiology, 236(2), 465–472. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010446

Pache, T. D., Wladimiroff, J. W., de Jong, F. H., Hop, W. C., & Fauser, B. C. J. M. (1990). Growth patterns of nondominant ovarian follicles during the normal menstrual cycle. Fertility and Sterility, 54(4), 638–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53821-7

KHAN-DAWOOD, F. S., GOLDSMITH, L. T., WEISS, G., & DAWOOD, M. Y. (1989). Human corpus luteum secretion of relaxin, oxytocin, and progesterone. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 68(3), 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-68-3-627

VERMESH, M., & KLETZKY, O. A. (1987). Longitudinal evaluation of the luteal phase and its transition into the follicular phase*. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 65(4), 653–658. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem-65-4-653